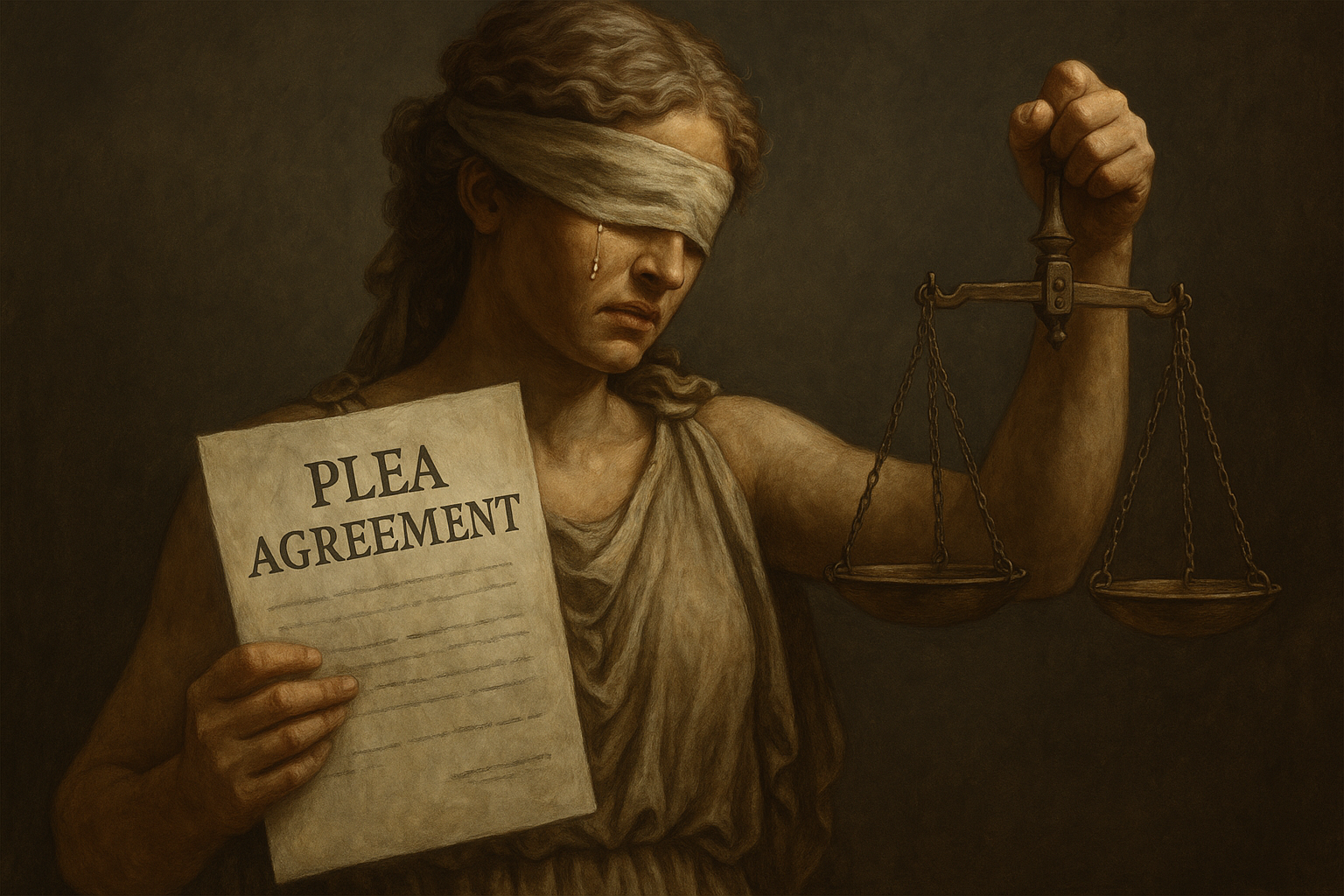

The State Thinks She’s Honest—So You Must Too: How the Indiana Court of Appeals Just Gave Prosecutors a Vouching Hall Pass

Walter v. State, or, "How to Make 704(b) Meaningless in 300 Easy Words"

Let’s set the scene: The prosecution’s star witness is a co-defendant who flipped, got a sweetheart deal, and now has every incentive to lie. You, as a defense attorney, want to show the jury this cozy arrangement to demonstrate bias and motive to curry favor with the State.

Good. That’s how it’s supposed to work. That’s literally why the law permits a defendant to bring in evidence of a plea deal.

But what happens when the prosecutor beats you to it—and decides to preemptively introduce the agreement themselves, complete with a letter spelling out that they only intend to call the witness if they decide she’s “truthful and honest”? What if the State puts that letter in front of the jury and then looks shocked—shocked!—when you say, “Wait a minute, that sounds like vouching”?

If you guessed the Court of Appeals would laugh that argument out of the room, congratulations—you’ve been reading Indiana appellate opinions long enough to develop Stockholm Syndrome.

Case Background: A Love Story Built on Theft, Fraud, and the Court’s Suspension of Disbelief

Before we rip into the legal absurdities blessed by the Indiana Court of Appeals in its July 16, 2025, opinion Walter v. State, 24A-CR-1786, let’s review the facts—because understanding how we got here is crucial to appreciating just how off-the-rails the Court’s logic went.

Meet Donald Walter, Jr. and his wife, Toni—a couple who apparently decided that if financial security wasn’t coming fast enough through honest work, they’d just write themselves a few checks. Or rather, Toni would, while Don managed the accounts. Because nothing says marital teamwork like synchronized embezzlement.

Toni had been the bookkeeper for a small business called Coogle Trucking in rural Benton County, Indiana since 2005. By 2013, she was fed up with the job, nearly quit, but was lured back by empty promises from the owners that things would change. Spoiler: they didn’t.

So, around 2016, Don floated an idea: “Why don’t you just take money?” Toni agreed. The scheme started small—extra checks here and there—but quickly snowballed into full-blown financial fraud. Toni began writing herself bonus checks and cutting fraudulent checks directly to Don. These were laundered through the company’s books to look like payments to legitimate vendors. Slick, right?

The couple operated two bank accounts: one for Toni at Staley Credit Union and one for Don at Regions Bank—cleverly referred to in trial as “Account 703,” a number that apparently became the financial equivalent of Voldemort in the courtroom. Don managed the money, paid the bills, and wrote checks off the stolen funds. In short, he played the CFO of the Walter Family Criminal Enterprise.

Things were going well. Really well. We’re talking about ATVs, cars, vacations, home renovations, and eventually, plans to build a new house. Toni kept the checks coming until COVID-19 hospitalized her in late 2020, interrupting the scheme’s cash flow. But after a brief period of forced financial austerity (during which they had to—gasp—sell some toys), Don got her back on the theft train. “All the fun toys came back,” Toni testified.

The couple even went so far as to take out a mortgage to build a new home—without disclosing Account 703 or the stolen income, which they also conveniently forgot to report to the IRS and the Indiana Department of Revenue. So not only theft, but mortgage fraud and tax evasion. A true trifecta.

Then, in mid-2022, Toni accidentally stumbled across an email on her boss’s account indicating she was being investigated. When she told Don, he didn’t exactly spring into cooperative transparency. Instead, he stormed out of the house, came back later, and began what can only be described as a gaslighting roadshow. He pressured Toni to take the fall entirely—coaching her on what to say, telling her to deny his involvement, and berating her when she wavered.

Eventually, the authorities got involved. The Indiana State Police executed a search warrant on their home. Don greeted them, watched them walk in, and then—like any totally innocent man—immediately left to go withdraw $80,000 and hand it over to his mother. (Because sure, that won’t look suspicious at trial.)

Both Don and Toni were charged. Toni flipped. And that’s where our story shifts from financial fraud to judicial farce.

To secure her cooperation, the State sent Toni’s attorney a letter outlining the terms of a plea deal. That letter included the State’s now-infamous caveat: “The State reserves the right to withdraw this proffer…until your client has testified truthfully and honestly at trial. It is within the State’s sole discretion to determine whether she is providing truthful and honest testimony.”

In plain English: if Toni didn’t tell the story the State wanted, the deal was off. But if the State liked what she had to say—and believed her—then she’d get the benefit of a capped sentence and charge reductions. It was a classic cooperation deal…with one twist: the State decided to introduce the letter itself at trial.

And when the defense objected—arguing, correctly, that the letter was a thinly-veiled endorsement of Toni’s credibility—the trial court shrugged and let it in. The prosecutor, apparently, could now tell the jury, “We’re only calling her because we think she’s truthful,” and call it “transparency.”

The jury convicted Don on multiple counts. But don’t worry: in its published-by-default memorandum opinion, the Court of Appeals gave its full blessing to the State’s use of this backdoor vouching technique, finding it totally permissible and even helpful to the defense.

Helpful?

That’s right. According to the Court, the State introduced the letter not to bolster their witness’s credibility—but to undermine it. To highlight her bias. To hand the defense a tool for impeachment. As if the prosecutor walked into trial thinking, “You know what? Let’s make sure we help the defendant score some points here.”

Because that’s totally how trials work.

Sidebar: What Is Rule 704(b), and Why Does It Matter?

Before we go any further, let’s break down exactly what Indiana Rule of Evidence 704(b) says—because the entire issue in Walter v. State turns on it.

Here’s the rule:

Indiana Evidence Rule 704(b):

“Witnesses may not testify to opinions concerning intent, guilt, or innocence in a criminal case; the truth or falsity of allegations; whether a witness has testified truthfully; or legal conclusions.”

Translation: No witness—including a prosecutor, law enforcement officer, expert, or your next-door neighbor—can tell the jury whether someone is lying or telling the truth. That’s the jury’s job. Period.

Why Does This Rule Exist?

Because we have this thing in our system called a “fair trial.” And central to that concept is the idea that jurors—not lawyers, not judges, not cops, not witnesses—decide who is credible and who isn’t.

If the government were allowed to put its thumb on the scale by telling the jury, “Hey, just so you know, we’ve vetted this witness and we think she’s being honest,” then the entire adversarial process falls apart. It becomes theater. The jury stops thinking critically and starts rubber-stamping whatever the State says.

Rule 704(b) was designed to prevent exactly that. It’s one of the only lines in evidence law that directly protects the jury’s exclusive domain—the determination of credibility.

But It’s More Than Just a Rule—It’s a Structural Safeguard

Think about it: if the State were allowed to openly say “we only make deals with truthful people” and then parade that person in front of the jury, what’s left of the defense’s ability to challenge credibility?

- Cross-examination? Undermined. The jury’s already been told the State trusts her.

- Motive to lie? Whitewashed. The jury hears that her honesty is why she’s on the stand in the first place.

- Bias? Defused. The State got out ahead of it and framed the bias as evidence of truthfulness.

This is exactly why courts—until now—have strictly policed efforts to bolster a witness’s credibility, especially by the prosecution. Courts routinely reverse convictions where a prosecutor crosses the line into direct or implied vouching. And for good reason. The prosecutor is the most powerful and authoritative voice in the courtroom. When they vouch, jurors listen.

But Walter v. State walks that line right off a cliff.

The Court’s “Helpful to the Defense” Theory: A Masterclass in Judicial Delusion

So, now that we’ve slogged through the saga of Don and Toni—the embezzling lovebirds turned courtroom adversaries—let’s get to the real head-scratcher: how the Indiana Court of Appeals managed to look at that prosecutorial cooperation letter and not see it as an endorsement of the witness’s credibility.

According to the Court, this letter—which explicitly says that Toni only gets her deal if the State decides she has testified “truthfully and honestly”—wasn’t improper vouching. Oh no. Instead, it was helpful to the defense. Their words, not ours:

“A reasonable juror could have interpreted the letter as a reason to treat Toni’s testimony with skepticism because she had a reason to minimize her own culpability and shift blame toward Walter.” (Walter v. State, slip op. at 9-10)

Stop and let that soak in.

The Court’s theory is that the prosecutor entered this letter not to convince the jury that Toni was trustworthy, but to alert the jury that she was potentially lying. That’s right—apparently the State was just doing the defense attorney’s job for them. Out of the goodness of their heart. Like some kind of bizarre reverse impeachment charity. We’re supposed to believe the State introduced this letter to undercut its own witness? That it essentially walked into court and said, “Here’s a letter that shows she has every incentive to lie—don’t believe her”? That’s like saying a magician reveals how the trick works halfway through the show just to keep things honest.

No one’s buying it.

It’s legal gaslighting in its purest form.

Let’s break down why this reasoning is so staggeringly absurd:

1. Prosecutors Do Not Undermine Their Own Witnesses. Period.

This shouldn’t have to be said, but here we are. The entire premise of a trial is adversarial. The prosecutor’s job is to win. That means building up their own witnesses, not sabotaging them. When the State introduces a document at trial, it’s because they believe it helps their case. They are not setting up a booby trap for themselves and hoping the jury steps on it.

The idea that the State entered this letter into evidence to make the jury question Toni’s credibility is so out of touch with courtroom reality it borders on parody.

Imagine a defense attorney walking into court and saying, “Here’s my client’s confession, your honor—I’d like to introduce it so the jury knows he might be guilty.”

You’d be laughed out of the courtroom—and rightly so. But the Court of Appeals would apparently call it “strategic transparency.”

2. This Letter Was a Classic Preemptive Strike

Prosecutors routinely try to defuse damaging impeachment by “getting out ahead of it.” It’s Trial Tactics 101. You introduce the cooperation agreement before the defense can, frame it on your terms, and signal to the jury: “Yes, she got a deal—but only because she’s cooperating truthfully. And you can trust her because we trust her.”

This wasn’t a confession of bias. It was a credibility cleanse. The letter practically screams, “We’ve already judged this witness to be truthful—and that’s why she’s here.”

The Court’s failure to see that for what it is—a thinly veiled endorsement—is either willful blindness or judicial complicity. Take your pick.

3. If This Isn’t Vouching, Then the Rule Is Meaningless

Let’s revisit Indiana Evidence Rule 704(b), which prohibits:

“Opinions concerning…whether a witness has testified truthfully.”

That includes indirect endorsements. That includes subtle nudges. That includes, and this is important, “We’re only offering her a deal if she testifies truthfully, and by the way, she’s testifying today.” That is the prosecutor walking into the jury box with a megaphone saying, “We believe her. You should too.”

The whole point of Rule 704(b) is to prevent the jury from outsourcing credibility determinations to the government. If you can now smuggle those determinations into evidence through cooperation letters written before trial, then the rule is dead. It’s just ceremonial language—like those “Speed Limit Strictly Enforced” signs that everyone ignores on I-70.

4. The Court’s Reasoning - Turning the Rule on Its Head

The Court’s rationale effectively eats itself.

- The letter says the State only wants “truthful” testimony.

- The witness testifies.

- The State introduces the letter.

- The jury hears, loud and clear, that this witness must have passed the “truthfulness test.”

- But according to the Court, the jury is supposed to read this as doubtful, not validating.

This is judicial logic by Schrödinger: the letter both proves and disproves the witness’s truthfulness, depending entirely on who’s asking.

This isn’t a legal analysis. It’s interpretive dance.

The Court’s Reliance on Brown v. State: A Case Misquoted, Misused, and Misunderstood

In attempting to justify its decision to allow the prosecutor’s cooperation letter into evidence in Walter v. State, the Court of Appeals cited Brown v. State, 587 N.E.2d 111 (Ind. 1992), for the proposition that “when the State has entered into a plea agreement with a witness it is necessary for the State to disclose such agreement.” That much is true—as far as it goes. But as with most things in law, the devil is in the omitted footnote.

To understand why the Court’s reliance on Brown is so deeply flawed, you have to trace the line of precedent the Court of Appeals blithely invoked. Because when you do, one thing becomes crystal clear: the original reason for requiring disclosure of plea agreements had nothing to do with helping the prosecution get ahead of impeachment and everything to do with protecting the rights of the accused.

Point One: The Lineage of Brown Begins with a Reversal for the Defendant

The Court in Brown cited Garland v. State, 444 N.E.2d 1180 (Ind. 1983), which in turn cited Newman v. State, 263 Ind. 569, 334 N.E.2d 684 (1975). And here’s the punchline: Newman reversed the conviction. Why? Because the State failed to disclose the existence of a leniency agreement with a cooperating witness. That omission deprived the defendant of the ability to effectively impeach the witness’s credibility—an error the Indiana Supreme Court found so significant that it warranted a new trial.

In Newman, the Court emphasized that “an accomplice who turns state's evidence…is being bribed,” and that the jury must be told about any such inducement because it “naturally impairs the credibility of such a witness.” The entire point was to protect the defendant by ensuring the jury knew when a witness had something to gain by testifying.

So yes, disclosure is required—but it’s required so the defense can use it to cross-examine, not so the State can launder credibility through the back door and then act surprised when the jury finds the witness believable.

Point Two: Brown Reversed the Conviction—Because of Improperly Admitted Content in a Plea Agreement

Even setting aside Newman, the reliance on Brown as supportive of the Court’s logic in Walter is a bit like citing a fire marshal's report as a defense for arson.

In Brown, the conviction was reversed because the State introduced a plea agreement that included a reference to the cooperating witness having taken a polygraph. The Court found that even referencing the fact that the test occurred (not the result—just the existence) created an inference that the witness had passed, and thus improperly bolstered his credibility.

The Court in Brown said it plainly:

“There can be no doubt that when submitted to the jury under the circumstances the only logical conclusion they could deduce would be that Ohm passed the polygraph test thus enabling him to complete his plea bargain with the State.”

The conclusion? Even if a plea agreement is otherwise admissible, that doesn’t give the State carte blanche to admit everything attached to it—especially if that material indirectly signals to the jury that the State has vetted the witness for truthfulness. In fact, the Court in Brown held that such statements must be redacted, and failing to do so was reversible error.

Now take a look at what happened in Walter:

- The letter said the State reserved the right to call the witness only if it determined her testimony to be “truthful and honest.”

- The State called the witness.

- The letter was introduced to the jury.

- The implication? The witness passed the State’s credibility screening.

How is that any different from implying a witness passed a polygraph? It isn’t. In fact, it may be worse—because it turns the prosecutor into both test administrator and credibility judge, all under the guise of a plea letter. If anything, Brown is a case for excluding the letter in Walter, not admitting it.

Point Three: “Disclosure” Is Not a License to Bolster

Yes, Brown and its predecessors say the State must disclose plea agreements. But “disclose” does not mean “bolster.” The purpose of disclosure is to allow the defense to explore motive and bias, not to give the State a pretext to introduce material that implicitly says, “We believe her.”

And even where a plea agreement is admissible, the form and content of that admission matter. In Brown, the problem wasn’t that the State disclosed the agreement—it was that the State included inadmissible content within the disclosure. The Court expressly held that where otherwise admissible evidence contains improper inferences, those portions “should be redacted.”

That same reasoning applies to Walter. Even if the plea agreement or letter was admissible for the limited purpose of showing motive or bias, the portion stating that the State would only call Toni if it believed her testimony was truthful should have been excised. Leaving it in was an implicit stamp of approval from the State on her credibility—and that’s the very definition of improper vouching.

The entire logic behind letting defendants introduce plea deals is that they’re evidence of bias. It gives the defense a tool to show motive to lie, cut a deal, and curry favor with the State. That makes sense. What doesn’t make sense is letting the State preemptively sanitize their own witnesses with documents that say, “Don’t worry, we’ve already decided this person is honest.”

What we’re left with is a new procedural monster: The State can now launder its witnesses’ credibility through conditional language in plea offers. Say it’s not explicit vouching and boom—admissible.

Apparently, all you have to do is slap “at the discretion of the State” on the end of a sentence, and suddenly you’re not putting your thumb on the scale. You’re just giving the jury “full context.”

The Court conveniently ignores the very premise behind admitting a cooperating witness’s plea: to impeach, not to sanitize. Letting the State introduce it to bolster their own witness’s believability is like letting the wolf wear a name tag that says. “Certified Sheep Inspector.”

The Policy Fallout: Congratulations, Prosecutors—You Can Now Vouch by Proxy

Here’s what Walter v. State really does, stripped of judicial lipstick: it creates a playbook for prosecutors to do precisely what Rule 704(b) forbids. It arms them with a fully court-approved strategy to vouch for their own witnesses, as long as they phrase the vouching as a “conditional” plea offer and date the letter before trial.

Don’t take our word for it—just follow the bouncing logic ball:

- The State crafts a plea offer that hinges on the witness testifying “truthfully and honestly,” as judged solely by the State.

- The State chooses to call the witness at trial.

- The implication becomes obvious: “We’ve determined she passed our truthfulness test.”

- The letter is admitted into evidence under the pretext of “transparency” and “bias disclosure.”

- The jury, being made of human beings with functioning brains, connects the dots.

What used to be improper vouching is now just “helpful context.”

The irony? The very logic that supports a defendant introducing a plea deal—because it reveals potential bias and self-interest—has now been weaponized by the State to preemptively sanctify its own witnesses. The rule has been flipped on its head. What was once a sword in the defense’s hand is now a shield in the State’s.

That’s not evolution. That’s regression.

Defense Attorneys, Take Note: This Will Be the New Norm

If you’re a criminal defense attorney in Indiana, go ahead and add this to your list of things to watch out for in trial:

- When you see that “cooperation letter” on the exhibit list, don’t assume it’s a harmless document. Assume it’s a trojan horse filled with vouching.

- Object under Rule 704(b)—and make your record loud and clear that admitting the letter implies prosecutorial endorsement of the witness’s credibility.

- Better yet, file a motion in limine ahead of trial to exclude any plea or proffer language that conditions the deal on a “truthfulness” determination by the State. Argue that such language, when introduced by the State itself, amounts to improper bolstering.

- And if the judge rolls over and admits it anyway, be prepared to write your own blog post—because this is the new frontier in appellate gaslighting.

Prosecutors Are Not Entitled to a Good Faith Presumption of Objectivity

The Court of Appeals in Walter seems to have forgotten a simple truth: prosecutors are not neutral actors. They are not there to do the defense’s job. They are not there to undermine their own case. And when they introduce a document at trial, it’s not to “give the jury tools to question the State’s case.” It’s to win. Full stop.

So when a prosecutor introduces a letter that says, “we only give deals to people we believe,” and then puts that person on the stand, that’s not self-immolation. That’s calculated bolstering.

And it’s now Court-approved.

What This Means for the Rule of Law (Spoiler: Nothing Good)

The whole point of rules like 704(b) is to prevent credibility determinations from being outsourced to power—especially to the State. When the Court pretends that jurors will infer bias from a letter that screams State endorsement, they’re not protecting the adversarial system—they’re neutering it.

This isn’t just a bad ruling. It’s an institutional wink. A quiet invitation to prosecutors everywhere: go ahead and vouch, just don’t be too obvious about it. And when the defense calls you on it, we’ll just pretend you were being generous.

Final Thought: The Law Says One Thing. Sometimes the Rulings Say Another.

If there’s a lesson in Walter v. State, it’s this: even the clearest of evidentiary rules can be contorted into something unrecognizable when the outcome demands it. Rule 704(b) wasn’t vague. It wasn’t ambiguous. It flatly prohibits opinion testimony about a witness’s truthfulness. Yet somehow, the Court found a way to carve an exception big enough to drive a fully-vouched witness through.

This isn’t just a quirky bit of legal gymnastics. It’s a warning shot to defense lawyers. If you’re expecting strict adherence to evidentiary rules that constrain the State, you may find that flexibility flows more freely in one direction than the other.

That doesn’t mean the system is corrupt. It means the system is full of people—and people come with instincts, biases, and yes, a certain gravitational pull toward the familiar and the comfortable. Prosecutors benefit from that inertia. Defense attorneys have to work twice as hard to overcome it.